In the summer of 1861, two dramatic but little-known Civil War skirmishes on the Virginia Peninsula saw one star fall and another rise.

Following Big Bethel, the first significant battle of the Civil War, Union and Confederate forces on the Virginia Peninsula settled into a stalemate behind their fortifications. Union forces occupied strong points at Fort Monroe and Camp Butler at the southern tip, while Confederates formed a line from the James to the York rivers. Both armies occasionally sent patrols into no man’s land to forage for supplies or scout for enemy activity, but neither was strong enough to dislodge the other.

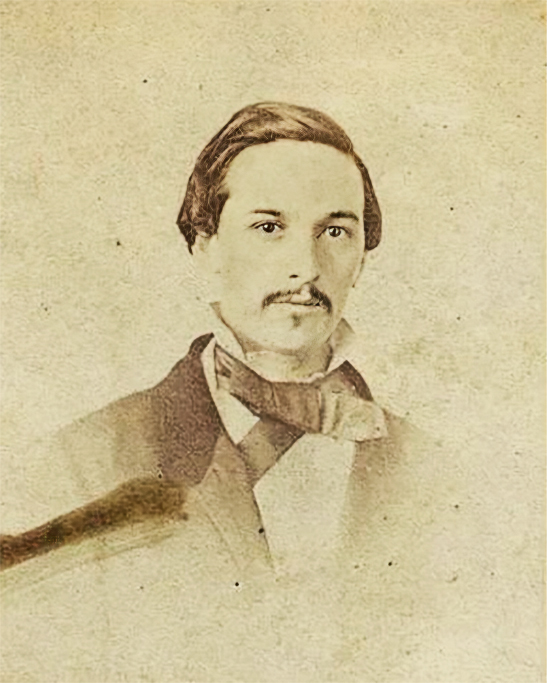

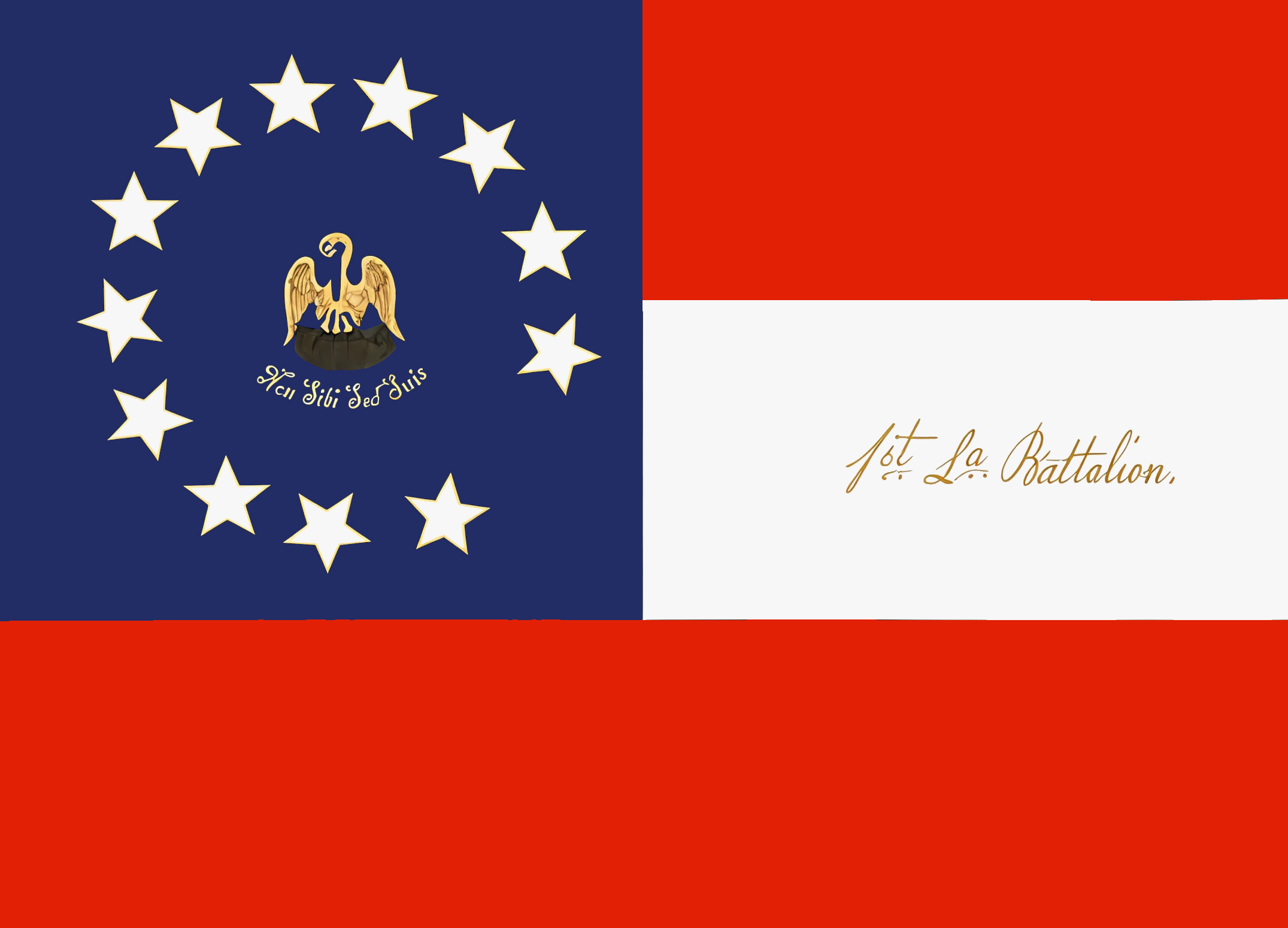

Newly promoted Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder, commanding the Hampton Division, assigned the 1st Louisiana Infantry Battalion to guard Young’s Mill, supported by a section of artillery from the 3rd Company, Richmond Howitzers, and cavalry from the Catawba Troop of Halifax County. Lt. Col. Charles D. Dreux of the 1st Louisiana took command of the camp. Young’s Mill was at a strategic intersection on the road from Warwick Courthouse to Newport News Point.

On July 4th, Independence Day, Dreux hosted a barbecue for his men, providing a generous supply of whiskey. He also welcomed Colonel Lafayette McLaws, the commander of Confederate forces at Yorktown, as a guest. Dreux gave a rousing speech, making it clear he did not intend to wait passively at Young’s Mill for the enemy. “This is our day, and we will have it,” he was said to have remarked.

Later that evening, during a meeting with his captains, Capt. William Collins of the Catawba Troop informed Dreux that Union troops were frequently seen at the home of Nelson Smith, located along the James River, about four miles to the south. Capt. Robert C. Stanard of the Richmond Howitzers suggested they take a detachment and set up an ambush, a plan Dreux wholeheartedly endorsed. Some sources claim that the idea for the ambush originated with Dreux himself. Regardless, the plan was set: after midnight, they departed with 100 infantry, 20 cavalry, and one howitzer.

As they neared a wooded lane running perpendicular to the main Warwick Road, near Smith’s Farm, Dreux positioned the howitzer down the lane, with the cavalry behind it and the infantry deployed on either side. They were ordered not to attack until the Union troops had passed. However, as sunrise approached with no sign of the enemy, Dreux grew impatient and sent scouts down the Warwick Road to determine their location.

Meanwhile, Capt. William W. Hammell and 25 men of Company F, 9th New York Infantry, had bivouacked a few miles outside their camp at Newport News Point. The 9th New York wore uniforms modeled after the French Zouave light infantry, consisting of dark blue pants and jacket with red piping, white leg gaiters, and a red Fez cap with tassel.

Shortly before dawn, they resumed their march northward. After about two miles, they were alerted to the Confederate presence when a Confederate private fired prematurely—some say at a snake—prompting Hammell’s men to spread out and return fire.

Capt. Collins reported, “The first information I received of the approach of the enemy, a gun was fired to our left, on the main road, and was immediately followed by another, and, with a short pause, the firing was again commenced about the same point, which was kept up regularly, the balls cutting around very near myself and men.”

According to Union accounts, at that moment, Lt. Col. Dreux stepped into the road and shouted, “Stop, stop for God’s sake stop—you’re shooting your own men!” If true (though Confederate accounts do not mention this), Dreux may have mistaken Hammell’s men for his own scouts, as they were far fewer in number than the large force he had expected. Hammell hesitated briefly, as the Louisianians’ uniforms resembled those of the 1st Vermont Regiment, but he then ordered his men to resume firing. Sgt. Peter J. Martin took aim with his rifle and fatally shot Dreux in the side.

The dense woods made visibility poor, and it seemed to the Confederates that fire was coming from all directions. In the chaos, Capt. Stanard ordered the howitzer to be limbered up and moved to cover the main road. The cavalry, misinterpreting this as a signal to retreat, surged forward, spooking the horses pulling the howitzer. The inexperienced driver lost control of the team, and the horses only stopped after the short skirmish had ended.

Realizing they were outnumbered, Hammell ordered Company F to retreat. Despite Confederate claims to the contrary, no Union soldiers were wounded in the fight. For the 1st Louisiana, however, the loss of their beloved “Charlie” Dreux was devastating. Dreux became the first field-grade Confederate officer killed during the Civil War, and thousands attended his funeral procession in New Orleans.

Eager for revenge, Confederates camped at nearby Young’s Mill sought an opportunity for action. Commanding the Confederate cavalry in the area was 30-year-old Maj. John Bell Hood, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. On the morning of July 12th, Hood led a mixed force of 125 men from the Old Dominion Dragoons, Charles City Troop, Dinwiddie Cavalry, Cumberland Light Dragoons, Mecklenburg Dragoons/Boydton Cavalry, and Black Walnut Dragoons, which collectively formed the nascent 3rd Virginia Cavalry Regiment. Hood and his men rode toward Union lines near the southern tip of Newport News, “looking out for a fight.”

Meanwhile, 36 men from Company E of the 7th New York Infantry Regiment had received permission to leave Camp Butler to gather firewood. The 7th New York was composed primarily of German-born immigrants from New York City, many of whom spoke little English. The regiment, known as the “Steuben Guard” in honor of Revolutionary War hero Baron von Steuben, had been involved in a friendly-fire incident during the Battle of Big Bethel when it mistakenly fired on the 3rd New York Infantry, which was wearing gray uniforms similar to those of the Confederates.

The 7th NY, like the 9th, adopted the Zouave style, wearing uniforms consisting of short blue jackets with red piping, baggy red trousers, white leg gaiters, and either a white turban or red Fez cap.

As the foraging party gathered firewood, a group led by 36-year-old Lt. Oscar von Heringen decided to venture deeper into the woods, moving closer to Confederate lines. They were spotted by Hood’s scouts near Cedar Lane and Nelson Smith’s farm sometime before noon. They were motivated to act outside their orders, it was said, by boredom and a desire to avenge their defeat at Big Bethel. Lt. Frederick Mosebach stayed behind with the rest of the party.

Hood mistook von Heringen’s patrol for an ambush and sent a detachment of 30 men, mostly from the Mecklenburg Dragoons, who were armed with Sharps breech-loading carbines, through the thick woods to confront them. Flanking von Heringen’s group, Hood’s men surprised Mosebach’s party, and a sharp skirmish broke out. Mosebach ordered his men to flee toward Nelson Smith’s house.

In Hood’s account, he recalled, “The enemy having been driven from cover in a very rapid and disorderly flight in the direction of Captain Smith’s house, on the banks of James River, I then ordered a charge, and the detachments … dashed gallantly down upon them, taking the flying enemy prisoners.”

Von Heringen’s patrol was cut off, and most of his men surrendered. The rest of Company E straggled back to camp. In total, von Heringen, Mosebach, nine privates, a mule, and a cart were captured. Four Union soldiers were killed, one mortally wounded, and several others wounded. The Confederates suffered no casualties, except for an injured horse.

Later, after the surviving men of Company E returned to camp, Lt. Col. Edward Kapff led 200 men from the 7th New York to the scene of the skirmish, but they found only scattered remnants of the battle.

The failed ambush at Smith’s Farm showed that alcohol and soldiering don’t mix, and that Charles Dreux’s brand of preening machismo is a liability on a real battlefield where things rarely go as expected and cooler heads prevail. The skirmish at Cedar Lane demonstrated the hazard of exceeding one’s orders and straying too far into enemy territory unsupported. Civil War armies had to learn these hard lessons repeatedly in the opening year of the war.

What are your thoughts?