In March 1864, political hatred on the Civil War home front exploded into deadly violence in Charleston, Illinois. The Charleston Riot reveals how Copperhead dissent, military repression, and personal vendettas turned neighbors into enemies far from the battlefields of the war.

On a pleasant spring day in late March 1864, members of the 54th Illinois Infantry Regiment gathered around a small-town courthouse, waiting to board a train that would return them to their unit. Tensions flared between the soldiers and a group of civilians who resented their presence, and soon shots rang out. The confrontation spiraled into a deadly riot, leaving nine people dead, including six soldiers, and twelve wounded.

This event did not unfold in Tennessee or Georgia, but in Illinois—hundreds of miles from the front lines. The Charleston Riot, as it came to be known, was the deadliest episode of Northern home-front violence outside the New York City Draft Riots. It is notable not only for its scale, but for its extraordinary aftermath, in which President Abraham Lincoln personally intervened to grant clemency to some of the rioters. The violence pitted antiwar Democrats against soldiers home on veteran furlough, their own neighbors. How, and why, did this happen?

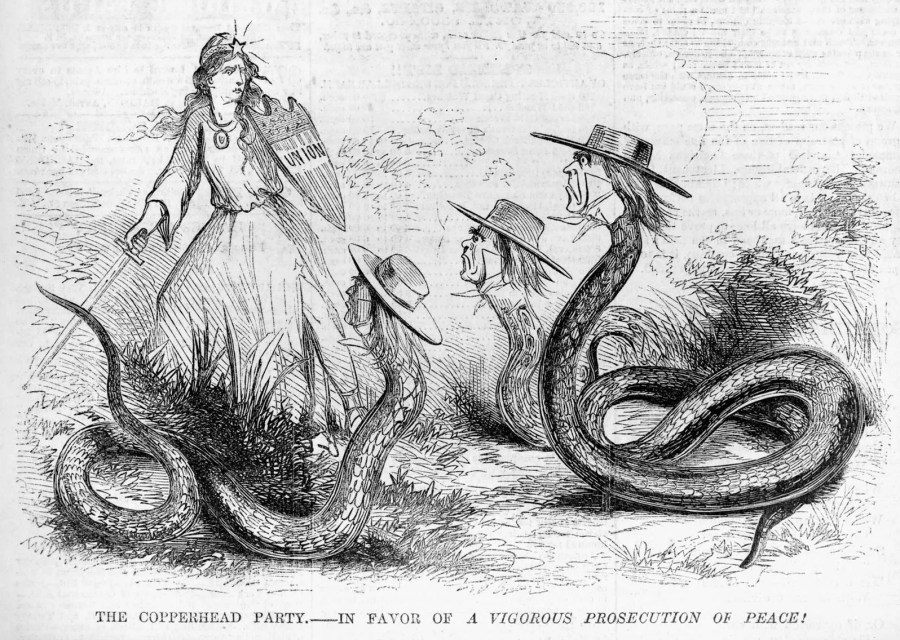

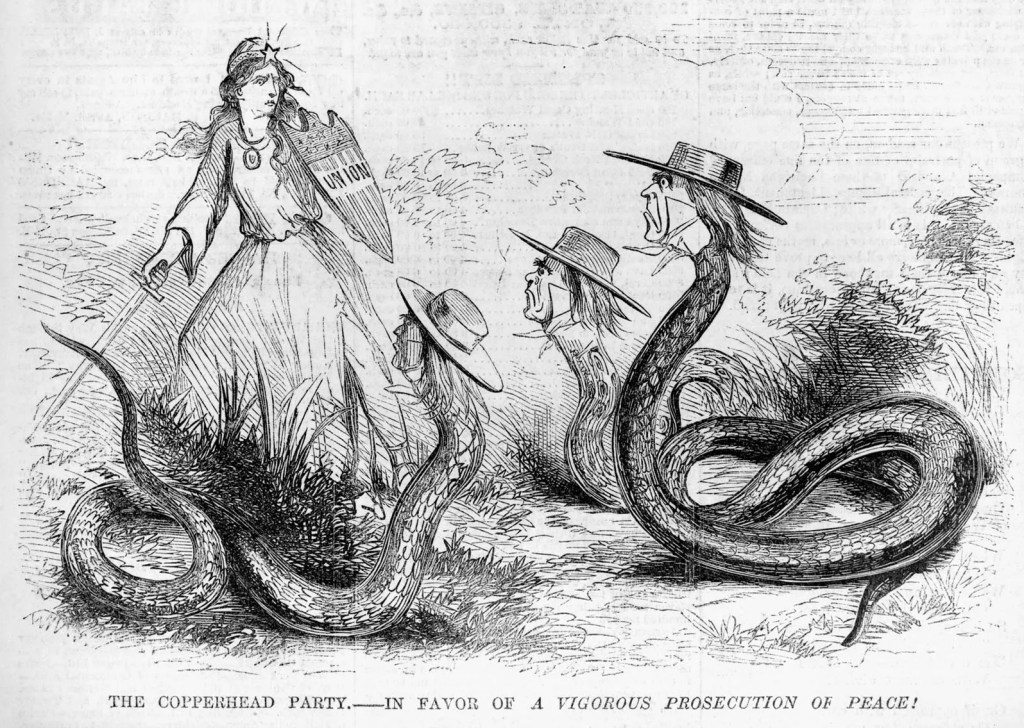

In 1864, as the Civil War dragged on and casualties mounted, public opposition to the war grew throughout the Northern states. The Northern Democratic Party sought to capitalize on this sentiment without providing ammunition to Republicans who already suspected Democrats of disloyalty. Walking this tightrope led the party to split into two informal factions, the Peace Democrats and the War Democrats. Peace Democrats, who opposed the war to varying degrees, were derisively labeled “Copperheads” after the poisonous snake. Some embraced the slur by defiantly wearing copper Liberty Head coins as badges of honor.

Copperheadism was a predominantly Midwestern phenomenon. Historians have long debated whether Southern kinship ties or economic connections best explain its appeal. Others, including Jennifer Weber and, to some extent, Frank Klement, have identified racial animosity as the primary motivating factor.[1]

My own research suggests that, at least in Illinois, Copperheadism had more to do with longstanding political rivalries than with economic or cultural ties to the South. Southern Illinois shifted heavily toward Unionism as the war progressed, exemplified by its most prominent general, John “Blackjack” Logan, despite the region’s overwhelming Democratic vote in the 1860 election. Central Illinois, where the margin between Republicans and Democrats was razor-thin, became the hotbed of Copperhead activity.[2]

Interest in Copperheadism peaked in the early 2000s, when historians drew parallels between Civil War-era opposition and contemporary resistance to the Iraq War. This interest culminated in Ron Maxwell’s 2013 film, Copperhead.

Several academic articles examining the Charleston Riot appeared during this period, including Peter J. Barry’s “The Charleston Riot and Its Aftermath” (2004), Stephen E. Towne’s “Such Conduct Must Be Put Down: The Military Arrest of Judge Charles H. Constable during the Civil War” (2006), Barry’s “Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist, and Copperhead” (2008), and my own “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois: Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864” (2012).

Other notable treatments include Robert D. Sampson’s “Pretty Damned Warm Times: The 1864 Charleston Riot and ‘The Inalienable Right of Revolution’” (1996) and Charles H. Coleman’s 1940 classic, “The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864.” Despite the Charleston Riot’s obvious importance to the broader story of Copperheadism and Northern home-front dissent, it has never received the national attention it deserves. All of these articles appeared in Illinois state historical journals.

The story of the Charleston Riot is the story of escalating political tensions in east-central Illinois during 1863 and early 1864. Although Abraham Lincoln won Illinois in the 1860 presidential election, opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation and the suspension of habeas corpus allowed the Democratic Party to gain a majority in the state legislature during the November 1862 midterm elections.

The passage of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act and the Enrollment Act of 1863, the nation’s first conscription law, further inflamed tensions, as Illinois Democrats attempted to pass resolutions and legislation calling for an armistice, restricting the use of the state militia, and obstructing the draft.[3]

One Democrat from Charleston, Illinois, voiced his frustration in the pages of the Chicago Times on January 25, 1863, writing, “History does not produce a more damnable and corrupt set of tyrants.”[4]

Republicans responded by accusing the Democratic Party of disloyalty, even treason. In February 1863, a state senator from McLean County in central Illinois, Isaac Funk, delivered a widely published speech in which he labeled his own colleagues traitors deserving of death. “They deserve hanging, I say, the country would be the better of swinging them up… What man, with the heart of a patriot, could stand this treason any longer?”[5]

In June 1863, Illinois’s Republican governor, Richard Yates, exploited a loophole in state law that allowed him to decide how long the legislature would remain in recess if the House and Senate failed to agree on a date. He prorogued them for two years and ran the state as its de facto dictator.[6]

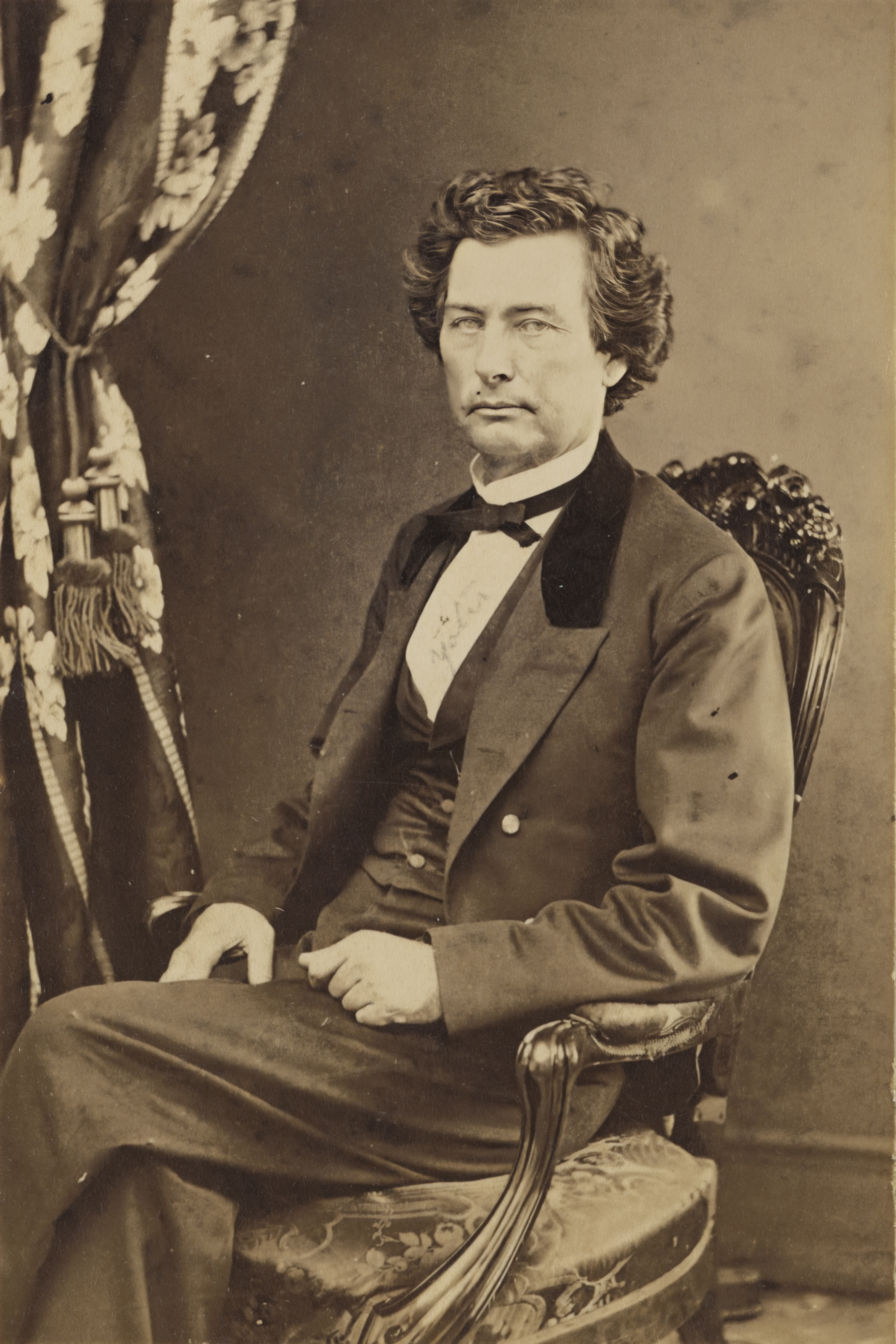

The political situation deteriorated further with the military arrest of Charles H. Constable, a judge of the Illinois Fourth Circuit Court and a onetime friend of Abraham Lincoln who, alongside Orlando B. Ficklin, had defended an escaped slave against Lincoln’s client in the Matson Trial of 1847.

In March 1863, Judge Constable granted a writ of habeas corpus to Union Army deserters arrested by Union soldiers in east-central Illinois and ordered their release. The Clark County sheriff then arrested the two sergeants leading the posse on kidnapping charges. In response, Colonel Henry B. Carrington led a force of more than 200 Union soldiers to Marshall, Illinois, to arrest Constable at the county courthouse while he presided over the sergeants’ trial. He was ultimately turned over to federal court, where the charges were dismissed.[7]

Constable became a cause célèbre among Peace Democrats and a target of derision among Unionists. On January 29, 1864, soldiers on leave in Mattoon, Charleston’s sister city in Coles County, forced Constable to kneel in the mud and swear a loyalty oath. The next day, Charles Shoalmax of the 17th Illinois Cavalry shot and killed a man named Edwards Stevens when he tried to escape the same fate.[8]

In February, tensions between Union soldiers on furlough and local Copperheads again boiled over, this time in Edgar County, east of Coles County. There, in the town of Paris, Amos Green operated a Democratic newspaper. Green was a member of the Order of the American Knights and helped organize the Sons of Liberty in Illinois. At a Democratic meeting in Mattoon in August 1863, he reportedly told the crowd, “They would appeal to the ballot-box for their rights, and if they could not get them in that way, they would appeal to the cartridge box.” Members of the 12th and 66th Illinois Infantry Regiments later forced Green to swear an oath and pledge a sum of money to prove his loyalty to the Union.[9]

In a confrontation on the streets of Paris, a soldier named John Milton York shot and seriously wounded an outspoken Copperhead named Cooper. The sheriff of Edgar County, William S. O’Hair, attempted to arrest the soldier, but one of York’s compatriots prevented him from doing so at gunpoint. York was eventually arrested, but the court released him on a technicality, and he rejoined his regiment.[10]

On hearing rumors that the soldiers planned to burn the newspaper office before returning to the front, Sheriff O’Hair, accompanied by more than a dozen men, rode into town on the day the furloughed soldiers were to leave. A young boy informed the soldiers of the posse’s whereabouts, and they immediately went to investigate. As they approached an alley, a group of men fired on them and then fled toward a horse stable on the edge of town, where Sheriff O’Hair and his posse were presumably waiting. According to the Daily Beacon-News, the men promptly escaped westward in the direction of neighboring Coles County.

As the soldiers approached the stable, Alfred Kennedy, a young man from Clark County who had been hiding inside, shot one of them in the wrist. Private Mark Boatman of the 12th Illinois peered into the building after hearing Kennedy call out that he surrendered. As Boatman lowered his weapon, Kennedy shot him in the shoulder. More Union soldiers arrived and poured a volley into the stable, riddling the planks with bullets and killing a nearby calf. When they looked inside, they found Kennedy badly wounded. Kennedy told the soldiers that his fellow Copperheads had planned to ambush them at the train station.[11]

Some of the participants in the Charleston Riot had familial ties to those involved in the February Edgar County affair. John Henry O’Hair, sheriff of Coles County, was William S. O’Hair’s cousin, and both were known for their Copperhead leanings. Major Shubal York, surgeon of the 54th Illinois, was from Paris and the father of John Milton York. These family connections meant that the violence in Edgar County had personal implications for key figures at the Coles County Courthouse on Monday, March 28, 1864, and would not be easily forgotten.

The Charleston Riot emerged not from spontaneous wartime tensions, but from a sequence of political provocations, personal vendettas, and escalating confrontations that had been building across east-central Illinois for more than a year. What began as ideological disagreements over emancipation and federal authority devolved into a bitter cycle of retribution involving military arrests, forced loyalty oaths, and armed confrontations between soldiers and civilians. By March 1864, conditions were ripe for violence. The deadly riot that followed was the inevitable culmination of months of political warfare that transformed ordinary citizens into enemies and reduced democratic debate to the language of bullets.

[1] Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 23; Frank L. Klement, “Midwestern Opposition to Lincoln’s Emancipation Policy,” The Journal of Negro History 49 (July 1964): 171.

[2] Michael Kleen, “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois: Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 105 (Spring 2012): 69-92.

[3] Willard L. King, “Lincoln and the Illinois Copperheads,” Lincoln Herald 80 (Fall 1978): 134-135; James J. Barnes and Patience P. Barnes, “Was Illinois Governor Richard Yates Intimidated by the Copperheads During the Civil War?,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 107 (Fall/Winter 2014): 338-339.

[4] Robert D. Sampson, “‘Pretty Damned Warm Times’: The 1864 Charleston Riot and ‘the Inalienable Right of Revolution’,” Illinois Historical Journal 89 (Summer 1996): 103.

[5] Loyal Publication Society, The Three Voices: Soldier, Farmer, and Poet. To the Copper Heads (New York: Rebellion Record), 1-2.

[6] John H. Krenkel, ed., Richard Yates: Civil War Governor by Richard Yates and Catharine Yates Pickering (Danville: The Interstate Printers & Publishers, 1966), 182-184.

[7] Stephen E. Towne, “‘Such conduct must be put down’: The Military Arrest of Judge Charles H. Constable during the Civil War,” Journal of Illinois History 9 (Spring 2006): 43-62.

[8] Sampson, 111; Charles H. Coleman and Paul H. Spence, “The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 33 (March 1940), 16.

[9] Peter J. Barry, “Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist, and Copperhead,” Journal of Illinois History 11 (Spring 2008): 48-49.

[10] Independent Gazette (Mattoon), 7 February 1864; Richard K. Tibbals, “‘There has been a serious disturbance at Charleston…’: The 54th Illinois vs. the Copperheads,” Military Images 21 (July-August 1999), 11.

[11] Crawford County Argus (Robinson), 10 March 1864; John Scott Parkinson, “Bloody Spring: The Charleston, Illinois Riot and Copperhead Violence During the American Civil War” (Ph.D. diss., Miami University, 1998), 168-71.

What are your thoughts?