The old Des Plaines Public Library on Graceland Avenue wasn’t just a place to check out books—it was a second home, a quiet sanctuary, and the backdrop to my childhood. Though the building is gone, its magic lives on in memory.

My family moved to Des Plaines, Illinois, a northwestern suburb of Chicago, in August 1985, just a few months before my fourth birthday. The Des Plaines Public Library quickly became a central part of my young life. I attended storytimes there, borrowed read-along books with cassette tapes sealed in worn plastic pouches, and spent countless hours exploring its shelves. My dad, a middle school teacher, often graded papers at the library. While he worked at a large round table, quizzes marked in red ink spread out before him, I immersed myself in books like the Usborne Time Traveler series.

When I was in elementary school, my mom started working as a library clerk. After school, instead of heading home, I’d walk to the library and wait for her shift to end. By high school, I’d joined the library staff as a page, shelving and organizing books. Over the years, the library became more than just a building—it felt like a second home. Despite spending so much time there, my family never took a single photo at the library. Even today, Des Plaines Memory—an online collection of local photos and stories—has only a handful of library images, and a request for pictures on the Facebook group “Des Plaines People Memories” turned up empty.

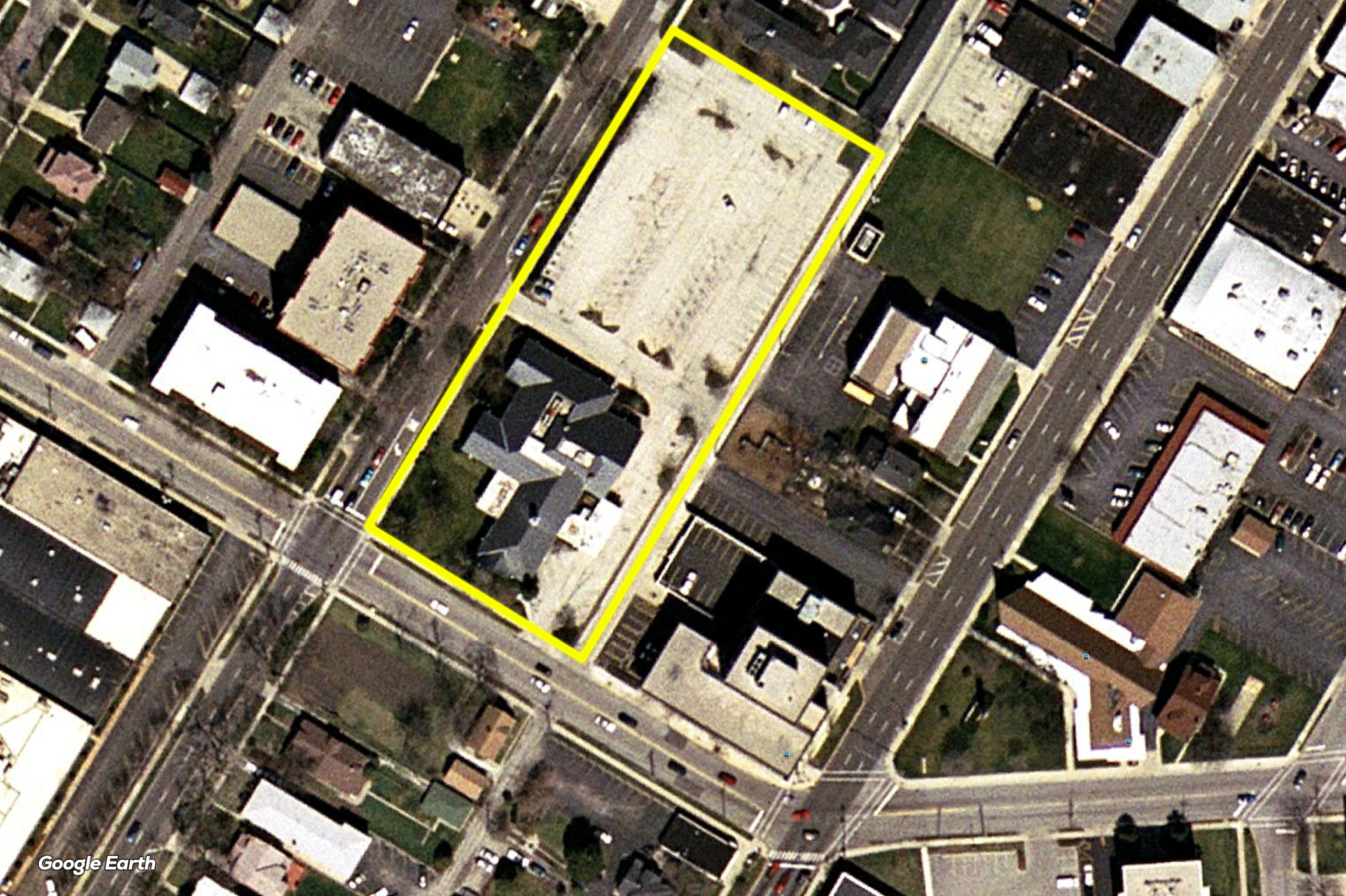

The summer after I graduated from high school in 2000, the city replaced this library with a four-story, state-of-the-art building at the site of the old Des Plaines Mall. The library at 841 Graceland Avenue (actually the city’s second–the first having been built in 1907) stood vacant for several years until it was demolished to make way for condominiums. This is my attempt to reconstruct the old library from memory.

Origins

The Des Plaines Public Library, built between 1957 and 1958, was a Colonial Williamsburg-style redbrick building with a tall white cupola and clock at the northeast corner of Graceland Avenue and Thacker Street. Originally 16,000 square feet, the library underwent two major expansions. In 1970, an office space and a garage to house the Bookmobile were added. Another 20,700-square-foot addition opened in 1974, more than doubling the library’s size.

The library shared an alley with Immanuel Lutheran School (now the Little Bulgaria Center) and the Des Plaines Tower office building. As a fifth and sixth grader at Central Elementary, I’d walk west along Thacker Street after school, past Immanuel Lutheran Church and across Lee Street. From there, I’d cut through the Lutheran School grounds to reach the library’s main entrance. In the 1980s and 1990s, you could stand near the school and see all the way to the traffic on Graceland Avenue, as nothing but a parking lot and some shrubs filled the space between.

Entering the Library

The library’s main entrance faced the parking lot at the back of the building. To the right of the door was a bike rack, where, despite leaving my bike unlocked many times, it was never stolen. A book drop was built into the wall. When patrons returned their books, they would land on a padded surface inside. Sunday afternoon was my least favorite shift because the pile of returned books waiting to be sorted always seemed overwhelming.

Upon entering, the circulation desk was on the right, while a stairwell leading to the basement was on the left. Straight ahead, past the security gate and a replica of the Liberty Bell, a short hallway led to the restrooms and elevator, and then to the main floor. Single-armed turnstiles controlled access, and book return slots were built into the wooden counter. That was where my mom worked and where we, as pages, sorted books onto carts to reshelve. There was always a flurry of activity, a smiling face, the dull knocking sound of books hitting the demagnatizer, and the click of the turnstile.

Adult Fiction and Non-Fiction, Reference Section, and Audio-Visual Room

The main floor was an irregular F or key-shaped space that included the original 1958 library and 1974 expansion. The “bar” of the F, what I call the northwest wing, was added in 1974. It housed the circulation area, fiction, non-fiction, and audio-visual sections. The “arm” was part of the original construction and housed the reference room and card catalogs. The “stem”, what I call the southwest wing, began at the reference desk and extended down to the magazine and newspaper area.

Turning into the northwest wing from the entrance, a stairwell on your right led to the mezzanine above, which held non-fiction books organized by the Dewey Decimal System. At the top of the stairs was the second-floor elevator door. A railing extended along the mezzanine so that you could look out over the main floor and see the activity below. When you reached the top of the stairs, the elevator was to your right and a computer to search the library catalog was on your left.

The non-fiction floor was divided into two spaces. To the left, the wooden bookshelves were lined in rows perpendicular to the railing. Books numbered 000–099 (computer science and information) started at the far end of the mezzanine and increased the closer you got to the elevator. Books on philosophy, psychology, religion, social sciences, language, science, comics, and art were all in these stacks. In the second space, next to the elevator, the shelves were at a 90-degree angle to those in the first. Here were your books on literature, history, geography, and biography. Two-person study carrels lined the walls behind the shelves.

Beneath the mezzanine, rows of shelves stacked with novels aligned parallel with the wall behind the circulation area. Several large tables were out on the floor, and metal storage containers with long drawers for maps lined the opposite wall. At the far end of the wing, a large, paneled window framed by heavy curtains let in light. Doors to the reference room and a second staircase to the mezzanine were located here, along with an open entrance to the audio-visual room.

The audio-visual room was a treasure trove of VHS tapes, records, and CDs. Several windows along the far walls let in natural light. Rows of alternating tall and short wooden shelves held everything from British TV series (Dark Shadows, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and Doctor Who) to my favorite documentary series like Ken Burns’ The Civil War and Classic Images: The Civil War 125th Anniversary Series. Records and CDs were in rows of waist-high wooden display shelves in the center of the room, arranged by genre. The music collection, while not cutting-edge, included artists like David Bowie, Metallica, and Hüsker Dü. The room had its own staff desk where patrons could check out audio-visual materials.

Returning to the entrance hallway, straight ahead was the southwest wing, home to the U-shaped reference desk where the reference librarian sat. Behind the desk, a door led to the employee office area and the Bookmobile garage, which had been added in 1970. This was where we entered for work and punched our timecards.

Directly across from the reference desk were two large card catalog cabinets and several narrow, rectangular tables. The walls in this recessed space were lined with bookshelves, which shared a dividing wall with the northwest wing. By the 1990s, the traditional card catalog—with its rows of tiny cards hand-typed with book titles, authors, and call numbers—was becoming obsolete. Several computer-based catalogs had taken its place, running on simple, text-based programs.

A large paneled window behind the card catalogs offered a view into the reference room. Patrons accessed the room from two directions through twin double doors. I didn’t spend much time there among the phone books and business directories, but my dad and I would occasionally visit to plan road trips. Before MapQuest, books were published annually that listed hotels and amenities located at every interstate exit—a handy resource for travelers.

Adjacent to the card catalogs was a small room that housed copy machines or possibly a microfilm reader. Next to it stood the library’s original entrance, though the door had been permanently closed by then, so I rarely had a reason to go over there. I remember one, maybe two, pay phones in the small foyer and a stairwell leading to the basement. At the far end of the southwest wing was the magazine and newspaper area. Along the southeast wall, there was a mezzanine with bookshelves both above and below. I’m not certain what books were kept there, but I believe they may have been foreign language or large print. In the far southeastern corner, a room that originally held copy machines was converted into a small computer lab in the late 1990s.

The Basement / Juvenile Section

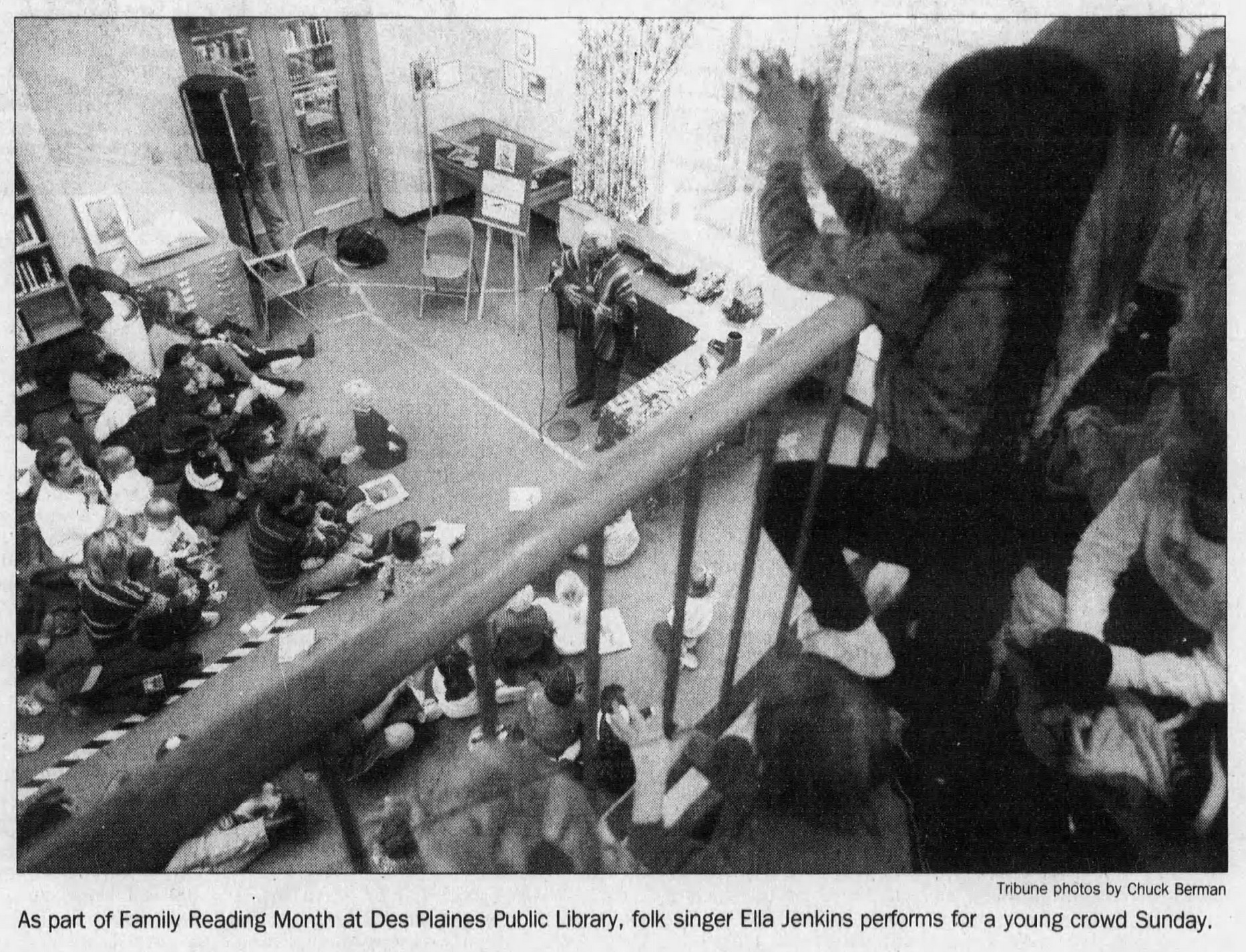

After descending the stairs from the main entrance, you entered a hallway with a display case along the right-hand wall. The displays changed weekly or monthly, depending on the holiday or program being promoted at the time. Opposite the display case were the entrances to a large event room and the elevator. Nearly every weekend, the event room hosted something—used book sales, free movies, presentations, or children’s events. I even participated in a talent show there once, proudly showcasing my Lego creations.

The children’s section in the basement was divided into two large, connected rooms. A wall separated the spaces, but wide entrances on either side allowed patrons to move easily between them. Coming from the elevator, the children’s librarian’s desk was immediately to your right, on the other side of the hallway wall. Across from the desk stood a large rectangular fish tank. Just beyond the librarian’s desk were four or possibly six IBM computers, equipped with a small collection of DOS games on floppy disks from the 1980s. You could play classics like King’s Quest, Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?, and my favorite—a text-based Civil War simulator from 1983.

A long, low bookshelf, about chest height, stood roughly three feet from the divider wall, creating a space for oversized books, atlases, and other reference materials. Globes and large dictionaries rested on top of the shelf. Nearby, a catalog computer was positioned close to the fish tank. In the open area, five or six round tables were arranged, and a ceiling-high paneled window filled the space with light from an exterior sunken entryway. The exit door had been sealed long ago, its alarm active and the ground-level gate permanently locked, creating a “secret garden” frozen in time. Rows of juvenile and young adult fiction and nonfiction shelves were angled throughout the room, while Celebrity READ posters lined the back wall.

The other, smaller room was dedicated to toddlers and elementary-aged children. Its construction-paper-lined walls were always adorned with some kind of artwork or themed decoration. In the center, a few kid-sized tables provided a space for young readers, while waist-high bookshelves lined the far wall. At the end of each shelf, there were displays featuring newly added or recently returned books. Audiobooks and children’s music were kept on this side of the divider wall. Library pages worked behind a horseshoe-shaped area made of desks and bookshelves, where we sorted children’s books and prepared them for reshelving.

Beyond this workspace, a hallway led to a kitchen and break room. The sparsely furnished break room consisted of an old couch and a large table. When I started working as a page in late August 1998, I was making $5.90 per hour, which was slightly above minimum wage. When I left 14 months later, I was making $7.15. There were other generous benefits as well. We got an hourlong lunch when we worked all day Saturday, and a 20-minute break for every four hours. The job was routine and not difficult, and I enjoyed working there. Most of my fellow pages were either current or former Maine West High School students, so I was always among friends. Two of my coworkers even ended up getting married. But it turned out that I enjoyed the library too much to work there. I’d rather check out books than reshelve them.

When it comes to names and faces, my recollection is hazy, but a few stand out. In the mid-to-late 1990s, Sandra Norlin was the library administrator. She served in that position from 1994 until 2010. Roberta Conrad was head of the children’s department. The reference librarian, Penny Sympson, was relatively young (mid-30s), petite with short red hair and glasses. Barbara Saletnik, the mother of one of my elementary school classmates, sadly passed away in 2008. My own mom, Linda Kleen, passed in 2014.

The Des Plaines Public Library was more than just a building—it shaped my childhood and connected me to my family, my community, and an entire world of stories. It was a second home where I spent my formative years. It wasn’t just a solitary experience but intertwined with family and friends. Those spaces, with their card catalogs, cheesy celebrity posters, and clunky IBM computers, might not seem extraordinary to someone who never experienced them, but to me, they were magical. They were the setting for moments—small and big—that made up years of my life.

Libraries like the one in Des Plaines aren’t just repositories of books; they’re community hubs, quiet sanctuaries, and shared memory keepers. Even now, as technology has replaced card catalogs and VHS tapes, the essence of what a library offers—connection, discovery, and belonging—remains timeless. It feels strange to realize that I have no photographs of the place that meant so much to me, a space that now only exists in memory. Preserving that memory matters because places like this deserve to be remembered not just for their function, but for the lives they touched and the stories they created. They remind us that simple places can hold extraordinary meaning.

Donate

Enjoy what you read? Please consider making a one-time donation to support my research.

Enjoy what you read? Please consider making a monthly donation to support my research.

Enjoy what you read? Please consider making a yearly donation to support my research.

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyMany thanks to the City of Des Plaines FOIA officer, library historian John Lavalie for digging up some photos for reference, and to friends and former coworkers for spot-checking my shoddy memory.

What are your thoughts?