Films like W. and Vice show how Hollywood attempts to shape our view of political legacies, revealing the power of film to influence how history is remembered.

The world of political biopics often seeks to illuminate the lives of leaders, peel back the layers of power, and, more often than not, critique those at the top. W. (2008) and Vice (2018), films focused on President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney respectively, take audiences into the tumultuous world of the Bush administration, 2000-2008. Despite their shared political backdrop, these films diverge in tone, focus, and success in capturing their subjects. Together, they offer insight into how filmmakers interpret and critique political legacies—and where they stumble in doing so.

Oliver Stone’s W. paints a portrait of George W. Bush, the privileged yet aimless son of a political dynasty who ascends to the presidency against expectations. Meanwhile, Adam McKay’s Vice delves into Dick Cheney’s evolution from a Wyoming-born political underdog to one of the most powerful vice presidents in U.S. history.

Both men’s lives share thematic parallels—troubled youths, political mentors (Bush’s Karl Rove mirrors Cheney’s Donald Rumsfeld), and deep reliance on supportive wives. However, where W. portrays Bush’s journey as one of familial rebellion and faith-driven ambition, Vice explores Cheney’s shrewd, calculated power grabs and his willingness to bend democracy’s rules for his vision of national security.

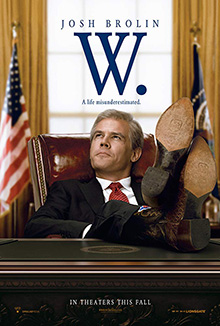

The tone is where W. and Vice most starkly diverge. Stone’s W. often feels like a satirical sketch stretched into a feature film. It leans heavily on caricature and comedic beats—Bush choking on a pretzel, his malapropisms, or his juvenile challenge to fight his father. This tone, while entertaining, risks undermining its message, inadvertently eliciting sympathy for its subject. Josh Brolin’s portrayal of Bush humanizes him, showing a man of genuine conviction, albeit misguided, rather than the bumbling buffoon Stone’s script often paints him as.

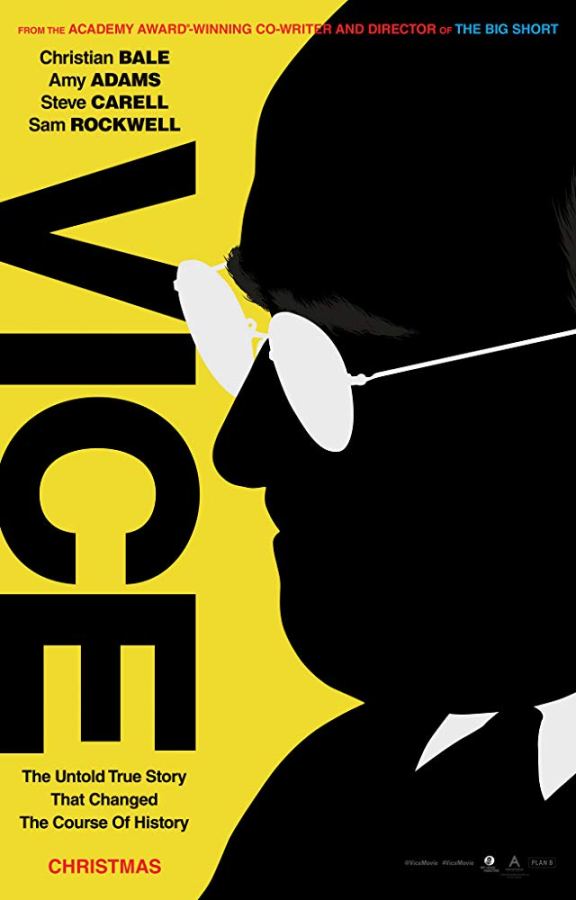

In contrast, Vice opts for dark humor and biting cynicism. McKay’s experimental style—breaking the fourth wall, inserting faux Shakespearean dialogue, and using montage sequences—heightens the absurdity of Cheney’s unchecked power. While these choices add flair, they sometimes distract from the narrative, leaving audiences to wonder if the spectacle overshadows the story.

Both films play fast and loose with history, selectively highlighting or excluding major events. The absence of 9/11 in W. is a glaring omission; it was arguably the defining moment of Bush’s presidency and a lens through which his policies—most notably the Iraq War—are viewed. By excluding it, W. feels incomplete, as though Stone sidestepped Bush’s brief moment of national unity to focus solely on his failures.

Conversely, Vice confronts 9/11 head-on, using it to underscore Cheney’s consolidation of power and controversial policies. Scenes of Cheney authorizing the shoot-down of hijacked planes or championing the Iraq invasion give weight to his actions, even as the film questions their morality.

Both films had clear objectives: W. sought to satirize Bush’s perceived incompetence and depict the Iraq War as a personal vendetta against Saddam Hussein, fueled by Bush’s need to outdo his father. Vice aimed to expose Cheney’s machinations and the broader consequences of unchecked executive power.

Where W. falters is in its lack of depth. It rehashes well-known moments from Bush’s life without providing fresh insight, making it feel like a collage of late-night talk show jokes from the early 2000s. By focusing too much on the man and too little on the policies, Stone misses an opportunity to explore the systemic issues that allowed Bush’s presidency to unfold as it did.

Vice, though more sophisticated, has its own pitfalls. McKay’s creative liberties—like the bizarre implication about Lynn Cheney’s father or the imagined Shakespearean dialogue—stretch credibility. While the performances (Christian Bale and Amy Adams in particular) are stellar, the film sometimes feels more like a partisan critique than a nuanced exploration of Cheney’s life and legacy.

Together, W. and Vice reflect the evolving narratives surrounding the Bush administration. W. emerged in 2008, as Bush’s popularity was at its nadir and public frustration with the Iraq War loomed large. It’s a product of its time, designed to lampoon an outgoing administration but inadvertently granting its subject a measure of humanity.

Vice, a decade later, benefits from hindsight and a cultural moment more attuned to exploring the dangers of centralized power. Cheney, who operated largely in the shadows, becomes a symbol of the executive branch’s potential for abuse. The film invites audiences to question not just Cheney’s choices but the system that enabled him.

Both films underscore how history is shaped not just by facts but by interpretation. Where W. feels dated, Vice resonates more deeply with contemporary concerns, but both leave viewers pondering the balance between satire and substance in political storytelling.

W. and Vice highlight the challenges of crafting political biopics. Both Bush and Cheney were controversial figures, and both films grapple with their legacies in markedly different ways. While W. struggles to go beyond surface-level satire, Vice risks alienating viewers with its stylistic excesses.

Ultimately, these films reveal as much about the filmmakers’ perspectives as they do about their subjects. They show how presidential administrations are remembered not only for their actions but for the narratives constructed around them—a reminder that in politics and film, perception often becomes reality.

What are your thoughts?