Following the Union occupation of Philippi, (West) Virginia in early June 1861, a black soldier was accused of shooting down an elderly man in cold blood. Who was he, and how did he end up in the Union army so early in the war?

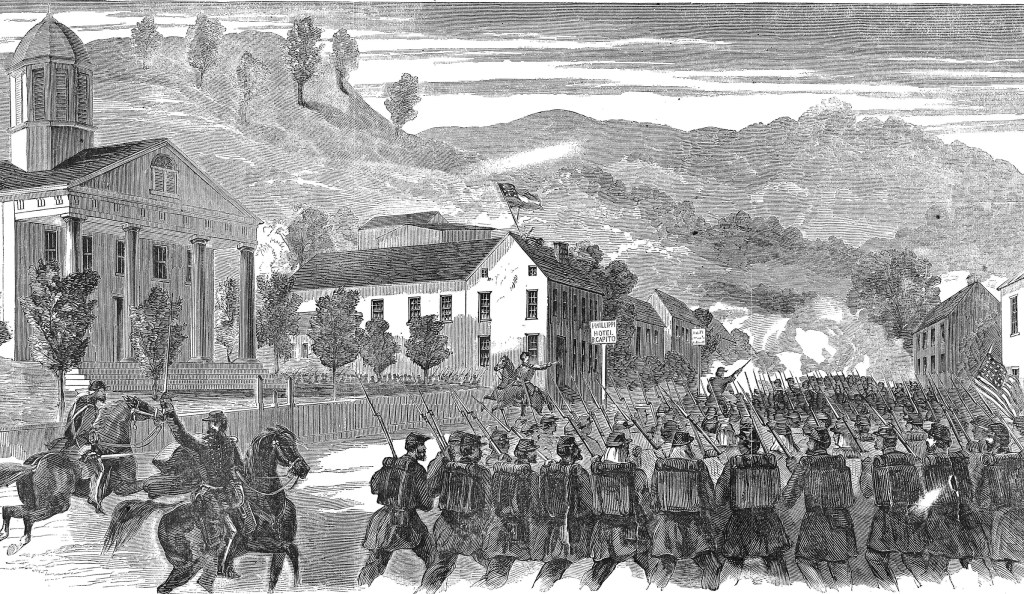

While researching early Civil War Virginia, I came across a surprising incident in the book Yanks from the South! involving a black Union soldier following the Battle of Philippi, which was among the first military engagements of the war. According to this story, a soldier named John Lott confronted an elderly man in the town of Philippi and demanded to know if he supported secession. The man answered in the affirmative, and Lott shot him down in the street in cold blood.

Fritz Heselberger, author of Yanks from the South!, does impeccable research, but there are reasons to be skeptical of this story. Primarily because the Second Militia Act of 1792 restricted U.S. militia members to “free able-bodied white male” citizens between the ages of 18 and 45, something that wasn’t amended to include African Americans until 1862. While Confederates did bring slaves and even freedmen with them on campaigns to perform menial labor, there simply were no black Union soldiers in 1861.

I had to know exactly where this information came from.

I found the original account in “The Spirit of 1861”: History of the Sixth Indiana Regiment in the Three Months’ Campaign in Western Virginia by A. J. Grayson. Its author, Andrew J. Grayson, was a sergeant in Company E, 6th Indiana Infantry Regiment. It’s not clear whether he was an eyewitness to the incident in question, but he was present in Philippi and had firsthand knowledge of it.

According to Grayson, “John Lott, of Madison, was the first colored man that shouldered a musket in the Union army, for I saw him standing in line with gun in hand and cartridge-box buckled to his hip when Capt. Gale’s company was drawn up in front of the Court House at Phillippi.”

Rufus Gale was captain of Company E, 6th Indiana. The 6th Indiana Infantry Regiment participated in the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861. Sgt. Grayson described John Lott as being a member of his company, but no one by that name is on the company’s muster roll.

Sometime after the Confederates cleared out of town, John Lott confronted an elderly black resident and asked if he was a “rebel”. The man answered in the affirmative, and Lott gave him fifteen minutes to “retract” his statement. Apparently the man refused, and Lott shot him in the chest, killing him.

“Was it murder? I think so,” Sgt. Grayson wrote. “Lott was arrested and lodged in the Court House along with the rebel that shot Col. Kelly, and afterwards they were both sent back to Wheeling and lodged in jail.”

It is difficult to verify Grayson’s account. No one by the name “John Lott” appears on the 6th Indiana muster rolls in any company. There is a “John Lott” in the 1860 census in Madison, Indiana, but he is around 13 years old and later censuses list his race as white. A search of Newspapers.com turned up nothing for that name or any variant of that name.

However, we were able to find several contemporary newspaper articles mentioning the incident. Unfortunately, they didn’t name names and several got the regiment wrong. They described the man as belonging to the “9th Indiana”. The 9th was also at Philippi, so it’s understandable that the regiments could be confused. Newspaper reports often mixed up regiment numbers.

The earliest newspaper report of the incident that I found was published in The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer on Friday, June 07, 1861, dated two days earlier. “Col. Crittenden’s servant, who killed the other negro, has not yet been executed.–There is a very bitter feeling against him among the men. They say this makes his eighth victim. He is part Indian, and a blood-thirsty sort of a devil, as this atrocious act testifies.”

A letter from Grafton in the same newspaper two days later states. “The negro who committed the murder at Phillippi, is also here in confinement.”

A more detailed account appeared in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial on Monday, June 10, 1861. “There were some excesses committed by the troops, after the capture of the town…” it read. It later continued:

“Three prisoners have been brought in from Phillippi: the redoubtable Col. Willey, Simmes, who shot Kelley, and a negro who, on Tuesday, shot one of his own color for calling him “a d–d Secessionist.” … The negro looks as though he had Indian blood in his veins. The negro killed by him is said to be his third victim, though it is known that in one instance he was justified in shooting down his man. He wears a red hunting shirt, fringed with buckskin, a slouch hat looped up at one side, and is altogether an ugly looking customer. He will doubtless be turned over to the civil authorities.”

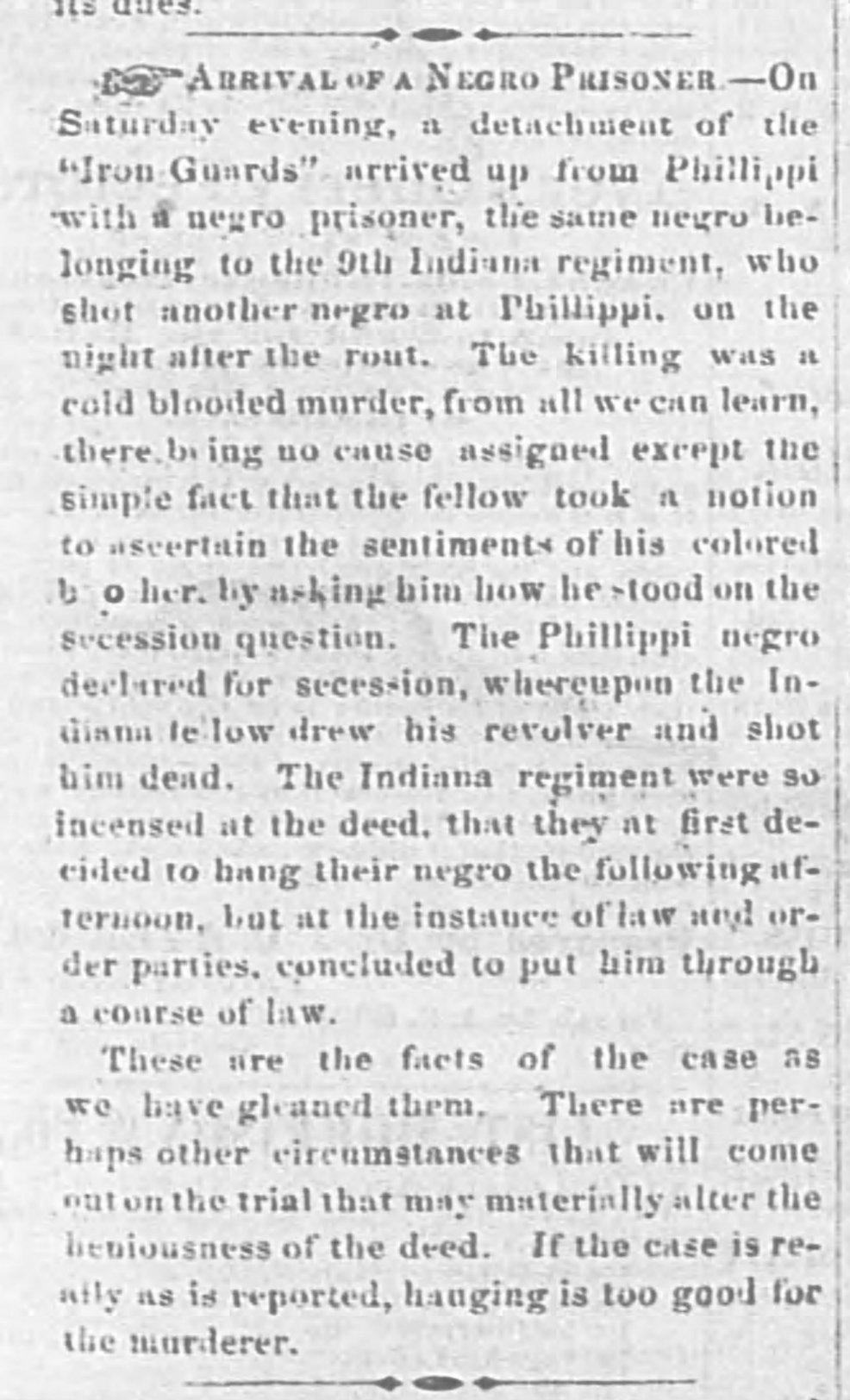

That same day, an article titled “Arrival of a Negro Prisoner” appeared in the The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer:

“On Saturday evening, a detachment of the ‘Iron Guards’ arrived up from Phillippi with a negro prisoner, the same negro belonging to the 9th Indiana regiment, who shot another negro at Phillippi, the night after the rout. The killing was a cold blooded murder, from all we can learn, there being no cause assigned except the simple fact that the fellow took a notion to ascertain the sentiments of his colored brother by asking him how he stood on the secession question. The Phillippi negro declared for secession, whereupon the Indiana fellow drew his revolver and shot him dead. The Indiana regiment were so incensed at the deed, that they at first decided to hang their negro the following afternoon, but at the insistence of law and order parties, concluded to put him through a course of law.”

The Intelligencer confirmed key details of Sgt. Andrew Grayson’s account, but, unfortunately, not the man’s name.

Later that month, Col. Frederick W. Lander, commander of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery, wrote a letter to the Intelligencer defending the conduct of the Union soldiers who stormed Philippi. “I cannot… deny that some unjustifiable acts were committed after the rout of the Secession forces at Phillippi,” he admitted. “They arose from a general break of the tired troops to search the town for Secession flags, and concealed men and munitions.” He did not, however, specifically mention a murder.

Sgt. Grayson wrote that, upon their return home to Indiana when their three-month term of enlistment expired, Major John Gerber stopped off in Wheeling and released John Lott from jail. “Lott was glad to see us looking so well,” he wrote. Contrary to the newspaper reports, it didn’t sound like the man was in danger of being lynched, or perhaps enough time had passed for those feelings to subside.

So who was John Lott, if that was even his name? He wasn’t a uniformed member of the 6th Indiana, being prohibited from enlisting by the Second Militia Act of 1792. Based on the description of his dress and the fact he was armed, he probably served as a scout. Men on this campaign often wrote about the dozens of scouts employed to patrol the mountains looking for enemy activity. It was a thankless task, and most of their names have been lost to history.

While Lott’s ultimate fate is unknown, being able to corroborate this story does lend it credence, and shows Andrew Grayson is a reliable source, even though he wrote his account over a decade later. It demonstrates that while African Americans were unable to enlist in the Union army in 1861, they did serve in other capacities and aided the war effort however they could under the circumstances.

Sources

- Daily Commercial (Cincinnati) 10 June 1861.

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (Wheeling) 7 June 1861.

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (Wheeling) 10 June 1861.

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (Wheeling) 20 June 1861.

- Grayson, Andrew J. “The Spirit of 1861”: History of the Sixth Indiana Regiment in the Three Months’ Campaign in Western Virginia. Madison: Courier Print, 1875.

- Heselberger, Fritz. Yanks from the South! The First Land Campaign of the Civil War: Rich Mountain, West Virginia. Baltimore: Past Glories, 1987.

- Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, 1861-1865, Vol. 4. Indianapolis: Samual M. Douglass, State Printer, 1866.

What are your thoughts?